| SDSS Classic |

| SDSS.org |

| SDSS4.org |

| SDSS3.org |

| SDSS Data |

| DR19 |

| DR17 |

| DR10 |

| DR7 |

| Science |

| Press Releases |

| Education |

| Image Gallery |

| Legacy Survey |

| SEGUE |

| Supernova Survey |

| Collaboration |

| Publications |

| Contact Us |

| Search |

Cosmic Clumping: Sloan Digital Sky Survey measurements of gas between the galaxies bolsters the case for inflation and dark energy, and improves the case limiting neutrino mass

CONTACTS:Prof. Uros Seljak, Princeton University, 011-386-31324750, useljak@princeton.edu

Dr. Patrick McDonald, Princeton University, 609-258-5858 pm@princeton.edu

Gary S. Ruderman, Public Information Officer, Sloan Digital Sky Survey, 312-320-4794, sdsspio@aol.com

(JULY 19, 2004) -- Using observations of 3,000 quasars discovered by the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS), scientists have made the most precise measurement to date of the cosmic clustering of diffuse hydrogen gas. These quasars--100 times more than have been used in such analyses in the past--are at distances of eight to ten billion light years, making them among the most distant objects known.

Filaments of gas between the quasars and the Earth absorb light in the quasar's spectra, allowing researchers to map the gas distribution and to measure how clumpy the gas is on scales of one million light years. The degree of clumping of this gas, in turn, can answer fundamental questions such as whether neutrinos have mass and what the nature of dark energy is, hypothesized to be driving the accelerated expansion of the universe.

"Scientists have long studied the clustering of galaxies to learn about cosmology," explained Uros Seljak of Princeton University, one of the SDSS researchers. "However, the physics of galaxy formation and clustering is very complicated. In particular, because most of the mass of the universe is made up of dark matter, an uncertainty arises from our lack of understanding of the relation between the distribution of galaxies (which we see) and the dark matter (which we can't see but the cosmological models predict)." The gas filaments seen in the quasar spectra are thought to be distributed very much like the dark matter, removing this source of uncertainty.

"We have known for several years that quasar spectra are a unique tool for studying the distribution of dark matter in the early universe, but the quantity and quality of the SDSS data have made that vision a reality," said David Weinberg of Ohio State University, a member of the SDSS team. "It's amazing that we can learn so much about the structure of the universe 10 billion years ago."

Seljak and his collaborators on the SDSS combined the analysis of the quasar spectra with measurements of galaxy clustering, gravitational lensing, and ripples in the Cosmic Microwave Background observed by NASA's Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP). This gives the best determination to date of the clustering of matter in the universe from scales of one million light years to many billions of light years. This comprensive view allows detailed comparison with theoretical models for the history and constituents of the universe.

"This is the most rigorous test to date of the predictions of the cosmological model of inflation; inflation passes with flying colors," added Seljak.

Inflationary theory states that right after the Big Bang the universe underwent a period of extremely rapid acceleration, during which tiny fluctuations were transformed into astronomical-sized wrinkles in space-time, ultimately observable in the clumping of astronomical objects. The theory of inflation predicts a very specific dependence of the degree of clustering with scale, which the current analysis strongly supports. Other scenarios, such as the cyclic universe theory, make very similar predictions and are also in agreement with the latest results.

Early analyses by the WMAP team and others had hinted at deviations in cosmic clustering from the prediction of inflation. If correct, this would have required a major revision of the current paradigm for origin of structure in the universe.

"The new data and the corresponding analysis substantially improves the observational precision of this test," said Patrick McDonald of Princeton University and one of the finding's authors. "The new results are in nearly perfect agreement with inflation."

"The clustering of matter is a precise and powerful test of cosmological models, and the present analysis is consistent with, and extends our previous studies," agreed Adrian Pope of The Johns Hopkins University, who led an earlier analysis of the clustering of SDSS galaxies.

The new analysis also provides the best information on the mass of the neutrino. Terrestial experiments--resulting in the 2002 Nobel Prize in Physics--have definitively shown that neutrinos have mass, but these experiments could only measure the difference in mass between the three different types of neutrinos known. The presence of neutrinos would affect the cosmic clustering on million-light-year scales, exactly the scales probed with the quasar spectra.

The new analysis suggests that the lightest neutrino mass has to be less than two times the previously measured mass difference. The new measurements also eliminate the possibility of an additional massive neutrino family suggested by some terrestrial experiments.

"Cosmology, the science of the very large, is able to tell us about properties of fundamental particles, such as neutrinos," said Lam Hui of The U.S. Department of Energy's Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, who has been carrying out an independent analysis of these data, together with Scott Burles of MIT and others.

The new analysis also provides further support for the existence of dark energy, and suggests that dark energy is unchanging in time. This analysis provides the best limits on its time evolution to date.

"No evidence of dark energy changing in time has emerged so far, and the possibility that the universe will be torn apart by a big rip in the future is substantially reduced by these new results," said Alexey Makarov of Princeton University, who also took part in this research.

|

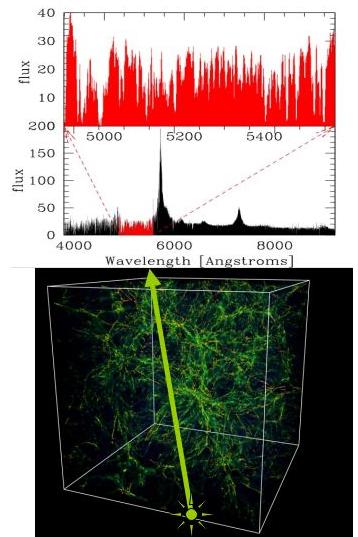

This figure shows the SDSS spectrum of a quasar at a distance of 12 billion light years. The middle panel shows the complete spectrum. The upper panel is an expanded view of the region of the spectrum affected by the filaments of gas whose clumping is the focus of the present study. Each of the hundreds of dips in the spectrum corresponds to a different parcel of gas along the line of sight between the quasar and the Earth. This is schematically shown in the lower panel, which indicates a line of sight through a simulation 30 million light years across of the distribution of gas in the universe. The clumpiness of the gas is determined by, among other things, the constituents of the universe, including dark matter, dark energy, and massive neutrinos. Renyue Cen of Princeton University carried out the simulation. |

The authors of the paper describing these results, to appear at http://xxx.lanl.gov/list/astro-ph/new on Monday, July 19, after 8 PM Eastern Time, are:

Uros Seljak, Princeton University, Princeton

Alexey Makarov, Princeton University, Princeton

Patrick McDonald, Princeton University, Princeton

Scott F. Anderson, University of Washington, Seattle

Neta A. Bahcall, Princeton University, Princeton

J. Brinkmann, Apache Point Observatory, Sunspot

Scott Burles, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Renyue Cen, Princeton University, Princeton

Mamoru Doi, University of Tokyo, Japan

James E. Gunn, Princeton University, Princeton

Zeljko Ivezic, Princeton University, Princeton

Stephen Kent, Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, Batavia

Robert H. Lupton, Princeton University, Princeton

Jeffrey A. Munn, U.S. Naval Observatory, Flagstaff

Robert C. Nichol, University of Portsmouth, Portsmouth, UK

Jeremiah P. Ostriker, Princeton University, Princeton

David J. Schlegel, Princeton University, Princeton

Donald P. Schneider, Pennsylvania State University, University Park

Max Tegmark, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia

Daniel E. Vanden Berk, Pennsylvania State University, University Park

David H. Weinberg, Ohio State University, Columbus

Donald G. York, University of Chicago, Chicago

ABOUT THE SLOAN DIGITAL SKY SURVEY

The Sloan Digital Sky Survey (http://www.sdss.org) is a joint project of The University of Chicago, Fermilab, the Institute for Advanced Study, the Japan Participation Group, The Johns Hopkins University, the Los Alamos National Laboratory, the Max-Planck-Institute for Astronomy (MPIA), the Max-Planck-Institute for Astrophysics (MPA), New Mexico State University, University of Pittsburgh, Princeton University, the United States Naval Observatory and the University of Washington.

Funding for the project has been provided by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, the Participating Institutions, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, the National Science Foundation, the U.S. Department of Energy, the Japanese Monbukagakusho and the Max Planck Society.